Phenomenal speech from Brandon Sanderson on the problem of AI and why the quality of it’s output (or even the source of it’s training) isn’t the issue.

Author: longwing

-

I hate The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.

For those unfamiliar. The Ones Who Walked Away from Omalas is a short “story” by Ursula K. Le Guin. It describes a perfect society who’s prosperity is dependent on the suffering of a child. It’s well loved, well regarded, and even taught in schools. It is, frankly, garbage that fails at every level. It’s a bad story, a ham-handed allegory, and an abdication of responsibility. I’m going to tell you why.

The Ones Who Walked Away from Omelas is often described as a “short story” and lumped in with speculative fiction. Most likely because Le Guin is well known for her SF work, and because it borrows some trappings of the genre. However, it is not a story at all. The bulk of the text is spent describing a fictional society called Omelas and laying out the rules. Everyone is happy, everyone is safe, everyone prospers, excepting “the child”. There is one child, locked in a windowless room and tortured. Everyone knows about the child. Other children are brought to the room to learn about the child. As long as the child suffers, Omelas prospers. To call Omelas a story is to describe any hypothetical as a story. There’s no plot here. No protagonist. No antagonist (save maybe Omelas itself). We’re given the situation, and then we’re told about those who “walk away from Omelas”, the ones who will not let their prosperity exist on the suffering of another.

We have a word for weird hypothetical situations designed to teach moral lessons: Allegory. Omelas is an allegory. Omelas is a rebuke of modern society. We prosper at the suffering of others, the poor within our own nations and the poor abroad. You are wearing clothing made by slaves, and you benefit from migrant labor that keeps your food prices low. Omelas cranks the dichotomy up to 11, showing us a perfect world and concentrating all the suffering into one child. What is the lesson that Le Guin wants to impart? The moral punctuation point at the end of the allegory? You should walk away. Leave modern society because it’s built on suffering. Le Guin was an Anarchist. She believed that the only right way to live was in lawless communes where everything is decided by consensus. I have serious disagreements with Anarchist thought, but that’s an argument for some other essay.

Lets leave aside Anarchism for a moment. Let’s instead talk about that that lesson, that “moral” message at the end of the allegory of Omelas. You should walk away. This society is unethical, so the only ethical thing to do is to leave. Go live on a commune with all of your Anarchist friends. My, what a lovely idea right? Just one teeny tiny problem…

They don’t take the child with them.

Gee. Must be nice to walk away, huh? The kid’s still locked in that room. Le Guin advocates leaving to form a better society… but the society you left is still there, and the child is still suffering. Omelas is a morally bankrupt allegory. Those who walk away still benefit from the suffering of the child, they got their resources from that suffering. Everything they take with them, every resource, their education, even their own bones, all of it comes from being raised in Omelas. When they can’t stand the raw deal dealt to the least among them… they abandon those least to their fate so they can wash their hands of the situation.

I can’t stand the praise lumped upon Omelas. It has the subtlety of a freight train and the kind of moral depth we always see from extreme ideologies “Things would be so much better if everyone thought/acted/believed exactly the same things I do!”. Sure, while we’re handing out wishes I’d like a Pegasus and the ability to create rainbows on demand.

We’re living in Omelas. There are legions of innocent people locked in that room.

Don’t walk away. They need your help. -

The competing priorities of combat in RPGs.

I just finished reading an incredible blog post at Knight at the Opera that attempts to aggregate “all” the different ways that games handle initiative and turn order. It’s a seriously fascinating read that I’d highly reccomend. Reading through it helped me sort out my mixed opinions about combat in RPGs. Simulating combat in an RPG means having to balance 3 competing priorities. Namely keeping the game moving, emulating a fight, and emulating “speed”.

Of the three I’ve listed, I think keeping the game moving is honestly the most important. A brilliant combat system is useless if it takes forever to execute. Over time I’ve increasingly come to believe that any combat system should handle player input in clockwise order around a table (or around the thumbnails of a video call). I used to hate this because it was “unrealistic”, but I’ve come to understand just how valuable it is to keep up the pace in a fight scene. Different games have different answers to this problem, but I think it’s absolutely key that you keep the game moving.

The second issue is actually emulating a fight, and stands in direct opposition to keeping the game moving. The more you work to make a fight “accurate” the more you have to bog down everything in minutia. A simple example of this is “to hit” rolls in D&D. They bog the game down and force players to simply miss a turn, all in the name of “accuracy” to how a fight can actually happen.

The final problem is the matter of “speed”. This isn’t universally addressed in RPGs. Some of them do it, others don’t, but many games try to figure out how to differentiate “fast” characters or actions from “Slow” characters or actions. This connects heavily to the question of emulating the fight. The more granular you get about fast/slow characters/actions, the more crunchy and emulate-y the combat becomes.

All of these exist on competing poles and work as part of a kind of tug-of-war. Pulling on one priority means taking valuable rope away from the others. I don’t have some miraculous solution to this problem, but realizing that these three things are fighting each other offers a clarity I’d previously lacked.

-

Fire on the Velvet Horizon’s incredible love letter to RPG Bestiaries

This isn’t a post about Fire on the Velvet Horizon, nor is it a post about how good Patrick Stewart (no relation)’s writing is. Perhaps some day I’ll do a full review of Fire on the Velvet Horizon. No, right now I want to talk about the back of the book, the space traditionally reserved for a sales pitch. Fire on the Velvet Horizon is (ostensibly) an RPG bestiary, illuminating the monsters of a campaign world that doesn’t exist.

Stewart put a poem here.

I am like no other thing.

A gem not famed for brightness.

Dead, but only listen and I live.

Voiceless, I speak.

Thoughtless, I lie.

Deeper than dark water.

Sharper than a swift sword.

Stranger than a drugged dream,

I serve in ordered ranks that never

change.

Till night,

When a gallery of shadows paints your thoughts,

with more colors than a careless artist’s hand.

Lose me or be lost in me.

I am a place you may not go.

Once there I will not let you leave.

Though made of broken things I am

yet whole.

And guard one hundred murders.

Let’s kill your friends for fun.Let’s all just stop a moment and bask in the sheer brilliance and the utter inscrutability of this poem… riddle… thing? You have to know RPGs. You have to know bestiaries. You have to be someone who’s poured through a Monster Manual page by page, daydreaming what it’d be like to introduce them to a game.

Let’s kill our friends for fun.

Damn that man can write.

-

Ruminations on using Tarot Cards for RPG Resolution Mechanics

I’m in the very early stages of developing an RPG around a core concept that leans on divination as a storytelling mechanic. As part of this I’m thinking about using a Tarot deck to resolve basic actions.

This is a tricky area that a number of games have tried to tackle over the years. Often the Tarot is suggested, but the problem is often that you need someone who actually understands the tarot to adjudicate results. Someone who’s not familiar with the meanings of the 78 cards in a Tarot Deck won’t be able to GM such a game, and asking a GM to train up on something that deep is a bit much.

I initially wrote some thoughts on this down in the RPG.NET forums… where it got basically no traction, so I’m reproducing my posts (from 15 SODDING YEARS AGO) here, on a site I own and control. I’ll likely revisit these basic ideas as I sharpen the concept.

Prior art

Of course, I’m hardly the first person to think of using cards for an RPG. Everway, Dragonlance 5th Age, Deadlands, Dragonstorm, Pathfinder (and I’m sure quite a few others) have all toyed with the concept or accepted it whole. Indeed, even the use of Tarot cards is non-unique. White Wolf created an entire Ryder-Waite variant deck for Mage: The Ascension, and included rules for using the cards as character generation tools, adventure hooks, or random encounter elements.None of the systems I’ve looked at have given me quite the result I’m looking for. They all have quirks that make them not-quite-right. 5th Age, for example, seems interesting but insists on tying too many game mechanics to the cards. Your hand size is your level! Your cards are your health! Etc.

Other systems tend to be too fuzzy for my liking. Most tarot or tarot-like decks are designed as inspiration and idea-seeds instead of actual rules. The leading questions on Everway cards, for example. Or the nearly rule-less Mage Tarot. Pathfinder’s Harrowing deck does a better job of offering solid rules for a Tarot-like system, but it’s a lot more about making the fortune-telling “come true” in the game, instead of using them as an active action-to-action mechanical element.

My concept

My plan is to devise a game with most of the usual d20ish trappings. Maps, minis, character sheets, etc. I’m not trying for some “grand unification theory” where every element is replaced by cards. I just want to replace the dice. You can certainly do a lot more with cards, and I want to toy with some of the differences, but not to the exclusion of everything else.I intend to use them with a difficulty check system. A card is drawn or revealed, relevant modifiers from stats and skills are added or subtracted, and the result is compared to a target difficulty to determine success/failure. At it’s most simplistic, a tarot deck is basically a D14. However, things get statistically interesting when you add in the Major Arcana.

Structure of a tarot deck

A tarot deck contains 78 cards:

– 22 Major Arcana, numbered from 0 to 21

– 56 Minor Arcana in four suits

– Each suit consists of an Ace, numbered cards from 2-10, and four face cards, for a total of 14 cards per suit.Starting rules

I started with a few ground rules. First, I’m assuming Aces are high, not low, as most games (and tarot readings) treat aces as a good thing, treating them as a fumble seemed counter-intuitive. Second, I decided to treat the Major Arcana as a 5th suit instead of a completely different kind of card. This means you can normally draw a card valued between 2 and 15, or a card up to 21 if you draw a Major Arcana.Odds of Success

With the structure of the tarot, and my starting assumptions, we get the following statistical breakdown:Difficulty — Odds of success

Greater than 21 — Impossible without bonuses

21 — 1%

20 — 2-3%

19 — 4%

18 — 5-6%

17 — 7%

16 — 8%

15 — 15%

14 — 22%

13 — 27%

12 — 33%

11 — 40%

10 — 46%

9 — 52-53%

8 — 59%

7 — 65%

6 — 72%

5 — 78%

4 — 85%

3 — 91%

2 — 97%I’ve rounded all odds to the nearest percent (or split the difference when it’s close to the middle of a percent). Really, that’s close enough for my purposes. If anyone’s really obsessed, I can post the odds to two significant digits. Yes, they actually go a lot further than that, but even two decimal places is pretty intense overkill in my opinion.

With a statistical spread like this, the real range of available difficulties is basically 2 to 18. Your odds of drawing 18 or better are about equivalent to rolling a natural 20.

The clever twist

A traditional Tarot deck assigns a meaning to every card. These meanings can be distilled/converted to RPG actions with a little work. Bluff, for example, a reflex roll, an attack roll, a wisdom check, etc.I figure I can assign four such distilled tasks to each card. If a given card is played for it’s appropriate action, then the card “crits”. The player then draws the top card from the deck and adds the value of the two cards together. This makes the visual content of a card very interesting/important to a player, while still giving a solid rule base for GMs to easily and consistently track.

The Major Arcana

If a Major Arcana crits, it counts as an automatic success, akin to a natural 20. This keeps with the tarot tradition of Major Arcana cards being more potent without making them all-powerful. They only crit on their assigned tasks, and count as normal rolls at all other times. Of course, their numbers go higher, so they’re also slightly more powerful than the other suits even on a normal draw. This also reinforces the idea that they’re more “potent” than the Minor Arcana.Questions I haven’t answered

Here’s some of the questions I haven’t answered:

What about The Fool and The Mage?

If aces are high, then we wind up with two oddball cards, the fool and the mage. The Fool is numbered 0 in a tarot deck. The Mage is numbered 1. Normally, that’d group the mage with the Aces, but with aces high, they’re actually 15, which makes them equal in value to The Devil from the Major Arcana. I don’t know what I’m doing with these cards.

Hand or no hand?

If a player draws a card from the deck for every roll and plays it immediately, then the deck functions as a very complex die capable of rolls between 2 and 21. A hand gives the player a lot more control over the outcomes of their actions, plus it gives me a chance to add mechanics for hand-size, discard, and draw. However, it also eliminates some of the tension, making a game less random and more strategic (is that really a disadvantage?)No way to roll a 1?

The odds of drawing a specific rank of card is about 7%. With aces high, the odds of drawing the Mage (the only card numbered 1) is about 1%. So there isn’t a statistically reasonable fumble card.Fumbles through reversals?

In tarot readings, there’s a tradition of reading a reversed (upside down) card as the opposite of its intended message. This idea can apply to an RPG. I mentioned using simplified card-meanings as a way of determining crits; this same tactic can be used for fumbles. If a card is revealed upside down, then it fumbles for it’s defined tasks. A second card is then drawn and subtracted from the first. A player dodges the bullet if he’s drawing the card for a task not defined on the card. As with crits, it just counts as a normal draw if it’s not what the card is meant for.Fumbles with hands?

The reversal idea for fumbles works fine, unless players are using hands. If a player is using a hand, they’ll never play a card in a fumble position. You could have them flip a coin to determine right-side up or upside-down, but I think this’d just lead to frustration. Players would deliberately avoid the 50-50 risk of a crit/fumble by playing cards that never align to their task, which would erode the whole feel of using a Tarot deck to begin with.The big advantage of hands is allowing players to choose their fate. It’s a lot more fun for a player to play the right card on the right task, getting a deliberate crit and establishing a feel of fateful cards for fateful acts. If I have a mechanic for using hands of cards, I need some other way of defining those oft-hilarious “oh crap” moments.

That’s everything I came up with all those years ago, and I already see several things that my latter experience has refined/changed. We’ll see how I do on round 2 of considering these mechanics.

-

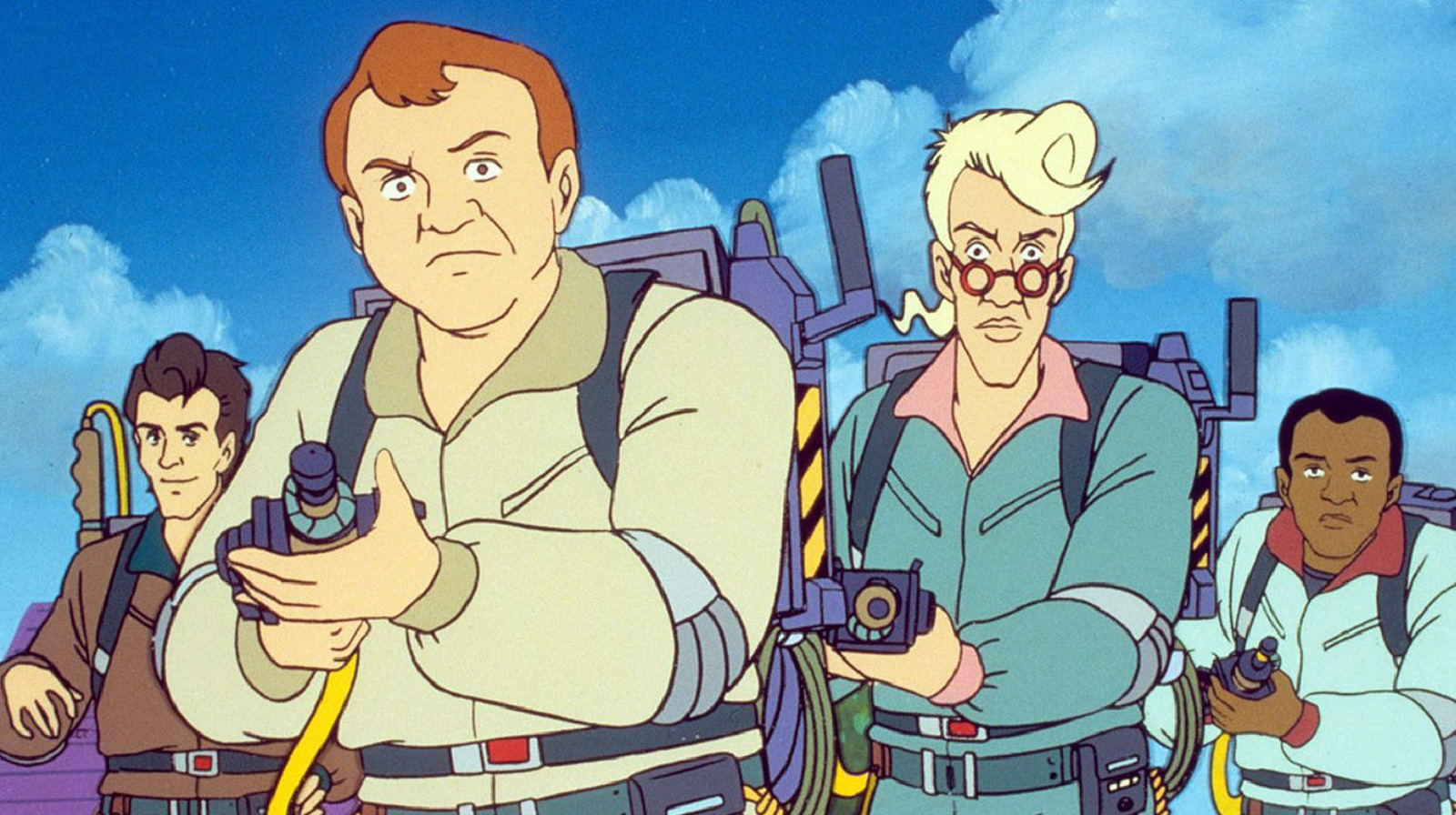

The Real Ghostbusters Animated Series Season 1 Episode Guide

I couldn’t find a good essential episode guide for The Real Ghostbusters animated series, so I decided to write one up. These reviews are entirely biased and wholly unscientific. Don’t like em? Make your own!

S1 E1 – Ghosts R Us (Skip) – This episode centers around the antics of a trio of ghosts who escape containment (?), pass themselves off as human (??), and then start a rival ghostbusting business to embarrass the Ghostbusters (???). The whole thing culminates with a different ghost possessing some toys and turning them into a giant monster that attacks Brooklyn bridge. The plot is nonsensical and the threat isn’t threatening. The only bright spot is the brief appearance of Ecto-2, a 2-seat helicopter that’s stored in the back of Ecto-1 (okay seriously who wrote this?).

S1 E2 – Killerwat (Maybe) – This one is… fine? The villain of the episode is a ghost named Killerwat who’s directing other ghosts to possess electrical systems. There’s a decent fight in a department store against some (legitimately creepy) possessed appliances, but that’s about all this episode has going for it.

S1 E3 Mrs. Rogers Neighborhood (Watch) – Now we’re talking! The Ghostbusters are called to investigate an old lady’s house. She’s terrified that it’s haunted, so they send her back to the firehouse while they investigate. Things aren’t what they seem and the Ghostbusters need to figure out what’s actually going on. Wonderfully threatening main villain and some actually creepy scenes.

S1 E4 Slimer, Come Home (Skip) – This episode was penned by J. Michael Straczynski (of Babylon 5 fame). As such, the banter and dialog are a lot better than other episodes. However, it’s still a Slimer-centric episode and those are a HARD pass for me. Slimer is a pest, and the other characters love/like him for entirely unstated reasons. He causes way more problems than he solves but he’s the designated “lovable” kids mascot. I first watched The Real Ghostbusters when I was maybe 8 years old, and I could tell I was being pandered to back then. Slimer grates all the more on my adult nerves.

S1 E5 Troll Bridge (Maybe) – A horde of Trolls take over a bridge after one of their number goes missing. The Ghostbusters have 12 hours to find and retrieve the wayward Troll before the rest of them invade. It’s a perfectly normal episode, but nothing really jumps out. The threat is goofy and not much interesting really happens.

S1 E6 The Boogieman Cometh (Watch) – The Ghostbusters are called in by a couple of children who are terrified of their closet. The terror turns out to be real, as their closet is a portal to the realm of The Boogieman, a supernatural creature that feeds on fear. Wonderfully creepy visuals and some nice Ghostbuster-y action sequences.

S1 E7 Mr. Sandman, Dream Me a Dream (Maybe) – The Ghostbusters go to investigate a case, only to find a slew of surreal happenings. Turns out a rogue Sandman has decided to stop giving normal dreams and instead make everyone sleep for 500 years. There’s some nice back-and-forth between the Sandman and the ghostbusters as the two sides try to beat the other’s plans. Unfortunately it’s impossible to take the Sandman seriously because the voice they gave him is so goofy.

S1 E8 When Halloween Was Forever (Maybe) – The ghostbusters face off against the original spirit of Halloween, Sam Hain. For some reason the animation quality in this episode drops sharply. It’s never great, but it’s noticeably worse here. The villain is fine, and there’s some neat parts to the episode, but I’d probably skip it.

S1 E9 Look Homeward, Ray (Maybe) – Ray heads back to his hometown in upstate New York to sit at the head of a parade. He meets his old crush and his high school buddy/bully. Shenanigans ensue. Ray gets made a fool of, but eventually saves the day. The level of high school drama in this one is cringe, and Ray’s motivations exist largely to service the plot. Dude quits being a Ghostbuster because of one embarrassing incident and decides… to be a mascot for a shoe store in his home town? He has a doctorate. Quitting doesn’t make sense, but even if he did he’d go back to academia, or open an occult bookstore or something. Despite all this, the plot is still stronger than a lot of Season 1 episodes.

S1 E10 – Take Two (Watch) – This one is kind of clever. The premise is that the live-action movies are based on the exploits of the Real Ghostbusters. It takes real hutzpah for the spinoff kids cartoon to tell a story about how the movies are dramatizations. For the premise alone, I’d say watch this one.

S1 E11 Citizen Ghost (Watch) – This episode is a flashback to right after the end of the first film. Some neat continuity (such as explaining why their uniforms changed in the cartoon and why the containment unit is bigger). It is, sadly, a slimer-centric episode, though maybe the most tolerable of them.

S1 E12 Janine’s Genie (Skip) – Janine asks to come with the rest of the team on a job, and manages to actually bag a ghost, but the building’s owner can’t pay them and gives her an old lamp instead. The rest of the plot unfolds exactly as you’d expect. Despite being Janine’s first time with a Proton Pack, I’d skip this one.

S1 E13 X-Mas Marks the Spot (Skip) – The Ghostbusters time travel (?) back to Victorian England and accidentally capture the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future (??). This alters the future, so they have to go back and fix the problem by releasing the ghosts (???). I mean, come on.

Final assessment

Out of all 13 episodes in Season 1, I’d only say that 4 are actually good. Even the “Maybe” episodes are merely serviceable. Mrs. Rogers Neighborhood, The Boogieman Cometh, Take Two, and Citizen Ghost are probably worth your time, but this season is definitely the series “finding it’s feet”.

Hopefully Season 2 will be better.

-

“Managing up” with a nightmare boss

There’s been a lot of talk in the news lately about Musk, Doge, and that horrible “Send me your 5 accomplishments” emails that everyone in government is getting. The world is spinning sideways and folks are rightly angry, but I’ve got some advice for anyone in a corporate job who will listen:

Do this anyways.

I started writing task reports years ago while dealing with a nightmare boss. They were a way of managing up, and I do it now with my current (Awesome!) boss too. Every friday, I compile a report that looks like this:

Hi boss, here’s my task report for $date to $date:

- Topic – Summary of what was done

- Topic2 – Summary of what was done

- Topic3 – Summary of what was done

For next week, my priorities are:

- Topic4 – Plan

- Topic5 – Plan

- Topic6 – Plan

Thanks,

MeI add as many bullet points as needed to cover whatever I did that week, and try to keep the next week down to less than three items (something always comes up anyways). Next week, whatever I put down for priorities becomes my top priority, so I can put them in the top half at the end of the week.

This worked wonders when dealing with my micromanaging moron of a boss. In fact, it worked SO well that he asked me to stop (I didn’t). He said he’d gained confidence that I didn’t need the oversight. In truth he was pissed off that every time he wanted to chew me out, the answer to whatever he was mad about was already in the report.

This tactic works even better when working for someone sane. My current boss never asks me what I’m working on because he already knows. If I’ve got a blocker, he knows about it. If he wants the status of something he checks the email.

When annual reviews come up, I go to my sent folder and pick out a page of “best of” entries from these reports to remind my boss of major accomplishments for the year, which leads to glowing reviews.

Everything going on with the US Government right now is a complete nightmare, and I have deep sympathies for anyone who’s manager thinks taking cues from the current administration is a good idea, but seriously, this tactic works wonders on incompetent managers.

It makes “what are you working on?” their problem, not yours.

-

RPG Review – Wildsea

A forest has consumed the planet. Trees the size of skyscrapers cover every inch of airable land. Only isolated mountaintops remain as proof of the ground far below. You command the crew of a chainsaw driven ship that “sails” this verdant expanse. Your crew are humans, cactus-people, humanoid insect colonies, and mushroom men. Not to mention the “weirder” members, like reanimated ship-golems, octopus people, and moth-folk. You are those who ply the rustling waves. Welcome to Wildsea.

Wildsea is an incredibly imaginative RPG packed with amazing weird fiction. I have some complaints with the included ruleset, but I also have to call out the book’s focus on approachability and it’s robust GM’s toolkit. For a book about such a weird world, it’s one of the most down-to-earth and approahable RPGs I’ve seen.

Let’s start with the world because the world of Wildsea is sodding fantastic. The whole surface of the planet has been choked over by a cataclysmic event called “The Verdancy”. This event claimed practically all low-elevation land, leaving only scattered mountaintops as viable refuge from the endless growth. Civilization exists only in dense pockets perched atop these precarious heights. Trade is handled by merchants who cross the dangerous Wildsea on ships rigged with massive chainsaws along their hulls. These chainsaw ships tear through the upper canopy, pulled along by immense metal teeth. The sea grows back behind them, so verdant that all evidence of damage is gone within hours. The players take the role of the crew of one of these ships. This world is rich with detail and ripe for adventure. I want to to play in it. but that brings us to the elephant in the branches: The rules.

While I adore the worldbuilding, I’m not the biggest fan of the “Wild Words” engine that fuels the fiction. The engine has some sound underpinnings, but I feel that the resolution mechanic is sadly lacking. Basically, Wild Words is a D6 “dice pool” system. You add 6-sided dice to a pool of dice based on your character’s stats, skills, and resources. You compile together your various advantages, then roll the dice. You then look for your highest roll. A 6 is a flat success, a 5 or a 4 is a success with a cost (lose resources, etc.), 3, 2, and 1 are failures that add a narrative complications. There’s some other rules, but this is the core of the system. The issue I have is with “The Cut”, which is how the GM (cutely/superfluously called a “Firefly” in Wildsea) can adjust the odds. The Cut takes away your best roll. So a Cut of 1 takes your highest die, a cut of 2 takes your 2 highest dice, etc. The problem with this system is that it’s mathematically kind of garbage. I may do a deep dive on it sometime, but basically it’s impossible to tell at-the-table whether a roll is easy, average, hard, or Very Hard. It’s a messy mechanic, and I like my resolution mechanics fairly clean.

Despite my complaints about the rules, I do have to applaud Wildsea’s approachability. Unlike a lot of other indy RPG products, Wildsea dedicates a good chunk of the book to training players and GMs alike in how to play, both how to play Wildsea specifically, as well as how to play RPGs in general. The book assumes you’ve never run an RPG before. One could argue that stance is staggeringly nieve, but it’s also refreshing to see a book that refuses to speak to the obvious audience of hardcore RPG fans. This book wants to be your first RPG, and critically, tries to make that easy. Even though I don’t agree with the ruleset, I’d highly reccomend reading this book just to glean it for ideas.

So can I reccomend Wildsea as an RPG? Sadly, no. I’ve got serious issues with the Wild Words engine that powers this product, and I just flat out think there are better RPG engines. However, it’s phenomenal worldbuilding and its sheer unrelentingly inclusive attitude stop me from writing it off altogether. GMs should read this book. Even if you’re never going to run it at a table, there’s too much good stuff in here to just ignore.

-

Starting from scratch

Time for a little reinvention. I gave up writing here because no one reads my stuff, but the modern era is showing me that it’s important to own and control your own content rather than relying on social media to host it for you.

And you know what? That’s why it’s called Sunken Library anyways. No one’s reading in a ruin.

So I’m going to start posting here again. Maybe once there’s a big enough body of work here I’ll shop it out to places where it’ll actually get found.